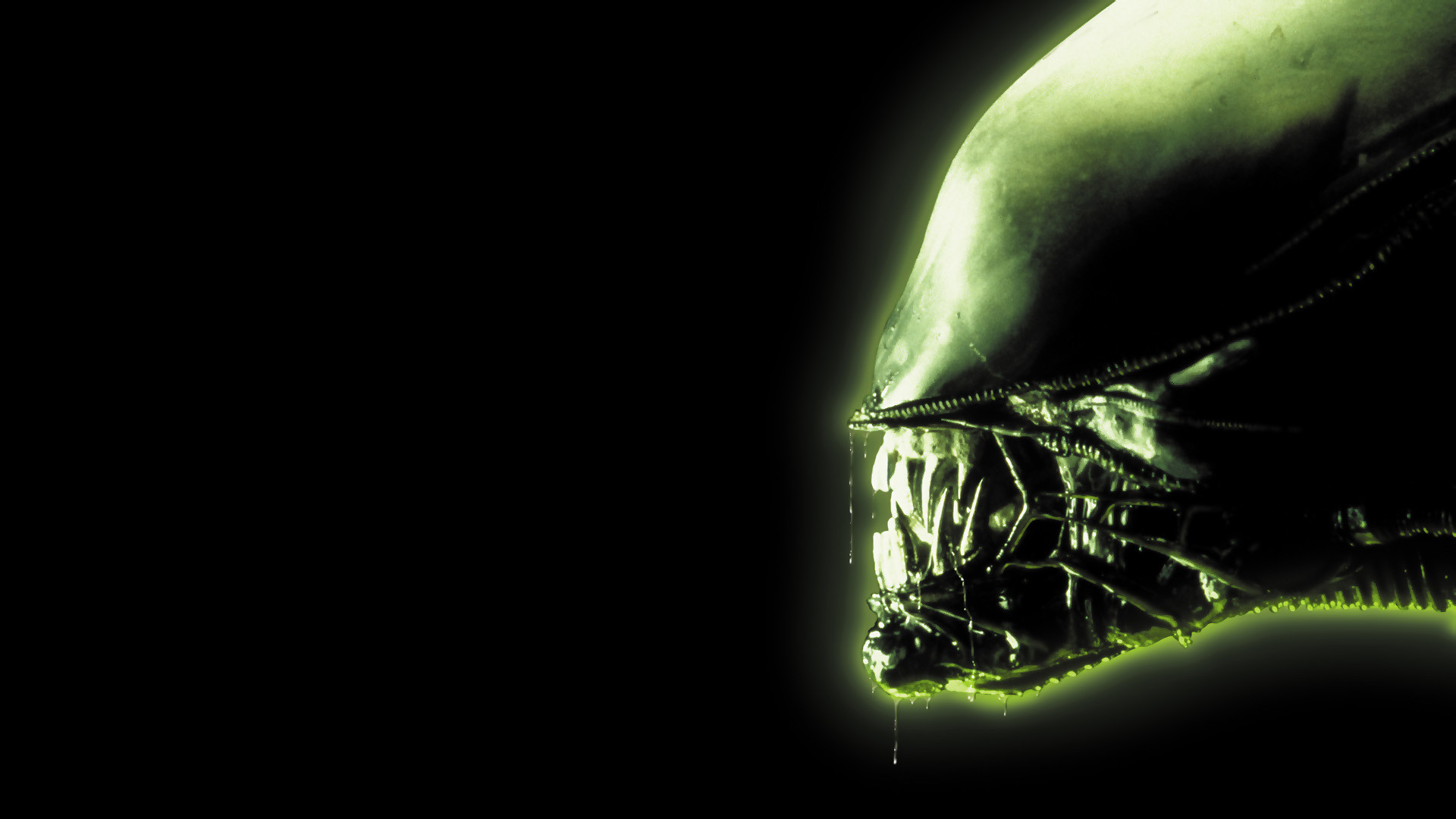

The original 1979 Ridley Scott sci-fi horror film has always stuck with me. It’s dark simplicity has never quite been matched by any of the sequels. It is the first time we are thrust into the unknown depths of space to witness the brooding violence of the Xenomorph. It is these original, glimpsed images of the horrific alien, as well as the anxiety brought through first contact, which I believe makes Alien the purest and most potent of the four (now five) films.

But which elements of the dreaded creature helped compose its infamy? What makes the Alien one of the most recognisable monsters in cinema? One aspect that can be seen throughout all of the films is how at home the Alien appears next to the cold backdrop of space. The creature looks as though it is biological adapted to the vacuum; its raw, natural and predatory form fits perfectly alongside all the images and ideas of a wild and lifeless outer-space. Unlike the romanticised space of other science fiction, Alien’s space is a landscape of cosmic horror – inert, dangerous and entirely uncivilised. It is a boundless, infinite space that human rationality cannot colonise, that the human mind struggles to comprehend. This makes space the perfect hunting/breeding ground for the abyssal Alien.

It is within the hollowed skeletal-cage walls of a derelict spacecraft that the Alien first appears. The spacecraft is however not the birth or home-world of the species. This lack of origin is important, as it’s an idea that, like death, can be deeply uncomfortable for human-beings who so often seek concrete answers. Repressed in the bowels of the ancient ship, hidden behind a veil of mist, lies the egg-room – where the Alien first leaps out from beneath pulsating and fleshy depths and latches onto the visor of John Hurt. It is only later, under the blinding lights of the medical lab that the creature becomes fully visible, its flat, sick-coloured body stretching across the crew member’s skull.

It is within the hollowed skeletal-cage walls of a derelict spacecraft that the Alien first appears. The spacecraft is however not the birth or home-world of the species. This lack of origin is important, as it’s an idea that, like death, can be deeply uncomfortable for human-beings who so often seek concrete answers. Repressed in the bowels of the ancient ship, hidden behind a veil of mist, lies the egg-room – where the Alien first leaps out from beneath pulsating and fleshy depths and latches onto the visor of John Hurt. It is only later, under the blinding lights of the medical lab that the creature becomes fully visible, its flat, sick-coloured body stretching across the crew member’s skull.

This face-hugging “Lamella” forces its proboscis down the victim’s throat and buries its monstrous foetus within the victim’s chest cavity, where it will begin to gestate. In essence the parasitoid Facehugger acts as the detached reproductive organ of the Alien, enveloping the faces of living species in order to disseminate its monstrous genes through the fertilisation of already-existing life. The detached nature of the Facehugger allows the fully grown beast to do away with sexual activity altogether, as it has no direct role in the reproduction process (this aspect was to be managed solely by the ‘Queen’ – a late addition seen only in the action-sequel Aliens, which significantly diluted the Xenomorph’s horrific power). This division of sexuality leaves the mature Alien to grow, expand, survive, and exterminate.

Whilst the Xenomorph is often described as embodying a type of raw libidinal energy, I see the Alien as an even rawer form, something possessing only a pure, mechanical survival instinct; a survival drive. The biomechanical warrior is undead, a meaningless function that propels the species quite mindlessly, and quite unconsciously, laying waste to its living competitors and dominating its space-habitat. Its existence is the enactment of a death drive. It straddles death, in order to thrive. What makes the Alien appear so unnatural, but also a luring visual spectacle, is the fact it exhibits these strange undead qualities. Its excessive drive to simply “live” is something we humans too evoke. Quite counter-intuitively, the Alien does not lack the natural life-processes for us to relate to, but instead contains an abundance of comparable biology. The creature contains a surplus of life: surviving, living, existing – along with an unrefined will for power and “being” – these are all some of the reasons why the monster appears so hideously alluring. What might another (perhaps more ‘civilised’) intelligent group of beings see when they look at us? Looking beyond our mass of social constructs and language games, perhaps they too would see ‘monsters’; beings willing to give up everything in order to survive. Like humans, the Xenomorph is ultimately and universally propelled by a set of shallow drives – to expand, grow, live and kill.

Whilst the Xenomorph is often described as embodying a type of raw libidinal energy, I see the Alien as an even rawer form, something possessing only a pure, mechanical survival instinct; a survival drive. The biomechanical warrior is undead, a meaningless function that propels the species quite mindlessly, and quite unconsciously, laying waste to its living competitors and dominating its space-habitat. Its existence is the enactment of a death drive. It straddles death, in order to thrive. What makes the Alien appear so unnatural, but also a luring visual spectacle, is the fact it exhibits these strange undead qualities. Its excessive drive to simply “live” is something we humans too evoke. Quite counter-intuitively, the Alien does not lack the natural life-processes for us to relate to, but instead contains an abundance of comparable biology. The creature contains a surplus of life: surviving, living, existing – along with an unrefined will for power and “being” – these are all some of the reasons why the monster appears so hideously alluring. What might another (perhaps more ‘civilised’) intelligent group of beings see when they look at us? Looking beyond our mass of social constructs and language games, perhaps they too would see ‘monsters’; beings willing to give up everything in order to survive. Like humans, the Xenomorph is ultimately and universally propelled by a set of shallow drives – to expand, grow, live and kill.

As a kind of incarnate nature the Alien also possesses the ability to transform itself through metamorphosis. This monstrous plasticity and biological mutability gives it an edge over its living counterparts, as the Alien is often in more of a state of becoming than actual being. All of these elements go some way towards explaining why, at the end of the original film, the on-board android admits an admiration for the creature’s purity. It is the “perfect organism” unbound by conscience, consciousness and delusions of morality. It is a form of life so natural and real, that when it bursts from the abyss beneath John Hurt’s ribcage, it allows us to see just how hollow our reality is. The Alien disavows human significance as quickly and as harshly as any film cut.